A Systematic Review

A. Raza, S. Mittal, G. K. Sood

J Viral Hepat. 2013;20(9):593-599.

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

The incidence of retinopathy in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with interferon-based regimens has been variably reported in the literature. There is no consensus regarding ophthalmologic screening before and during treatment with interferon-based therapy. To assess the incidence of retinopathy in patients with chronic hepatitis C being treated with interferon-based regimens and estimate the rate of resolution. A systematic literature search was performed to locate all relevant publications. Pooled incidence of retinopathy was calculated in patients treated with interferon or pegylated interferon. We also estimated the rate of discontinuation of treatment and resolution after the treatment was stopped. A total of 21 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The overall incidence of retinopathy using random effect model was 27.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] 20.9–34.5%). The pooled incidence of retinopathy in 10 studies that only used pegylated interferon was 20.9% (95% CI: 11.6–29.8). The incidence of retinopathy with pegylated interferon in diabetic and hypertensive patients (high-risk group) was 65.32% and 50.7%, respectively. This was significantly higher compared with the incidence of retinopathy (11.7%) in patients without these risk factors. Overall pooled estimate for the resolution of retinopathy was 87% (95% CI 75.7–98.4%). The rate of discontinuation of treatment was 6.3%. The incidence of retinopathy with pegylated interferon in patients without hypertension and diabetes is low, but the risk is higher in patients with diabetes and hypertension. Routine pretreatment fundoscopic screening may not be warranted in all patients and can be limited to the patients with these risk factors.

Introduction

In recent years, there have been significant advances in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. There are many new agents on horizon, and the novel interferon (IFN)-free regimens are being explored. But IFN-based regimens along with the new direct acting antiviral agents are likely to stay as part of hepatitis C treatment for the next few years.[1–3] Currently, pegylated interferon alpha (PegIFNα) is a part of all the standard regimens for the treatment of HCV. The development of retinopathy is a well-known side effect of the PegIFNα therapy.[4] However, the data report discordant results about the frequency and clinical significance of retinopathy seen during PegIFNα-based therapy. Retinopathy has been reported in 18–86% of patients with chronic HCV who received IFN-based treatment regimens, and the risk is even higher in diabetic and hypertensive patients.[4–6] The wide range of frequency reported in the literature reflects the limitations of small studies, which are heterogeneous in selection of the patients and screening protocols for retinopathy. Given the inconvenience and cost associated with the ophthalmological screening, significance of IFN-associated retinopathy during HCV treatment and lack of screening or surveillance protocols, we conducted a systematic review to estimate the incidence of retinopathy in patients with chronic HCV being treated with PegIFNα or IFNα and its outcomes. We specifically reviewed incidence in various high-risk groups, pertinently in patients with associated diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension (HTN). We also studied the rate of discontinuation of the treatment due to the development of severe retinopathy and the outcomes of retinopathy after the treatment was completed or discontinued.

Methods

Electronic databases (PubMed and Scopus EMBASE, ISI Web of Science) were searched for the studies between January 1991 and December 2012 by two independent investigators (AR and SM). The search terms used were hepatitis C, HCV, Interferon, interferon alpha, pegylated interferon, pegylated interferon alpha and retinopathy and their Boolean combination. The search was limited to the studies published in English. Related abstracts presented at meetings were also reviewed. In addition, a manual search was performed for cross-references from publications.

Study Selection

We selected the studies reporting the incidence of retinopathy in patients with chronic HCV, who were treated with IFNα or PegIFNα with or without ribavirin. We included both retrospective and prospective observational studies.

Following inclusion criteria were used:

-

Retinal examination performed at baseline, which is prior to the initiation of treatment or within 1 week of the initiation of treatment.

-

Retinal examination performed at least once during treatment and at least once after the discontinuation or finishing the treatment.

Studies were excluded if:

-

The patient population had co-infection with hepatitis B (HBV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

-

History of liver transplantation.

-

Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria for ophthalmological examination.

Outcome Measures

Following outcome measures were assessed

-

The pooled incidence of retinopathy in patients with chronic HCV treated with PegIFNα or IFNα.

-

The pooled Incidence of retinopathy in high-risk (patients with DM or HTN) and low-risk (patients without HTN or DM) groups treated with PegIFNα for chronic HCV.

-

The rate of resolution of retinopathy in patients treated with PegIFNα and IFNα.

-

The rate of discontinuation of PegIFNα and IFNα treatment.

Data Extraction

The data were systematically extracted and entered into the tables. The data included study type, year of publication, type of interferon used, retinopathy prior to the treatment, incidence of retinopathy on active treatment and the rate of resolution of retinopathy after discontinuation of the treatment. Retinopathy was defined as the presence of cotton wool spots, retinal haemorrhages or microaneurysm. Resolution of retinopathy was defined as disappearance of cotton wool spots, retinal haemorrhages or microaneurysms on the surveillance fundoscopic examination.

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

The incidence of retinopathy for each study was calculated using the number of patients who developed retinopathy and the total number of patients treated with IFN. Data analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel using methodology described in details by Neyeloff et al.[7] Proportions were compared using chi-squared test, and a P-value <0.05 was considered significant. Summary pooled incidence with 95% confidence interval (CI) was obtained. Heterogeneity was evaluated using Q statistic and I 2 index. To take the effect of heterogeneity into consideration, random effects model was used for analysis.

Results

After careful review of the literature and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, only 21 studies were selected (see Table 1 for all the citations). There was wide geographical spread; seven studies from Asia, six from Europe, five from USA, two from Africa and one study from Canada. Ten studies used PegIFNα, eight studies used IFNα, and three studies used a combination of PegIFNα and IFNα to treat the patients with chronic HCV (Table 1). Overall incidence of retinopathy was calculated in studies that used PegIFNα or IFNα either alone or in combination with ribavirin. Incidence of retinopathy was calculated in diabetic and hypertensive patients[4, 10, 11, 18, 25] as well as nonhypertensive and nondiabetic patients[4, 10, 18, 25] in the PegIFNα treatment studies that provided pertinent clinical information.

Overall Incidence of Retinopathy

There were a total of 1382 patients in 21 studies that received either IFNα or PegIFNα. The incidence of retinopathy ranged from 2.6% to 61.1% among studies using random effect model (heterogeneity I 2 = 17.9%). The overall incidence of retinopathy using random effect model was 27.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] 20.9–34.5%).

PegIFNα vs IFNα

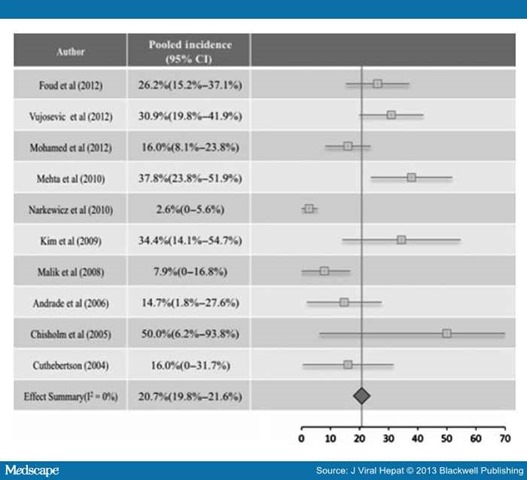

The pooled incidence of retinopathy in 10 studies (Fig. 1, 608 patients) that exclusively used PegIFNα was 20.7% (95% CI: 19.8–21.6). The pooled incidence of retinopathy in eight studies that exclusively used IFNα was 41.6% (95% CI: 28.8%–54.5%), which was significantly higher than PegIFNα-treated group (P < 0.0001).

Figure 1. The incidence of retinopathy in PegIFNα treated patients.

Incidence of Retinopathy in High-risk and Low-Risk Groups With PegIFNα Treatment

Only five of the ten studies[4, 10, 11, 18, 25] looked at the incidence of retinopathy in diabetic and hypertensive patients (Table 2). Among these patients, 84 had HTN and 38 had DM. Some of these high-risk patients had overlap of both diseases, but the information about this was not provided in all studies. The incidence of retinopathy in diabetic and hypertensive patients was 65.32% (95% CI: 39.6–91) and 50.7% (95% CI: 39.6–61.8), respectively (Table 3). Four of these five studies looked at the incidence of retinopathy in patients without HTN or DM.[4, 10, 18, 25] The incidence of retinopathy in this low-risk group was 11.7% (95% CI: 6.4–17). The incidence of retinopathy in diabetic and hypertensive patients (high-risk group) was significantly higher compared with the patients without these risk factors (P < 0.0001 and P < 0.0001, respectively).

Resolution of Retinopathy in Patients Treated With IFNα/PegIFNα

Estimates of resolution of retinopathy were reported in 17 studies (Table 1). Pooled data from these studies included 260 patients that developed retinopathy, of which retinopathy resolved in 233 patients. Pooled estimate for resolution of retinopathy was 87% (95% CI 75.7–98.4%). Data on resolution of retinopathy were reported in eight studies that used PegIFNα. Among 92 patients that developed retinopathy with PegIFNα, retinopathy resolved in 77 patients after completion or discontinuation of treatment. The pooled estimate of resolution was 81.9% (95% CI 63.4–100%). Resolution rate in subgroups (high-risk vs low-risk) was not performed due to small sample size.

The Rate of Treatment Discontinuation

Overall, 6.3% (n = 8) and 1.9% (n = 3) of the patients discontinued treatment in PegIFNα and non-PegIFNα groups, respectively. Reasons to discontinue the PegIFNα treatment included patient request (n = 4), retinal vein occlusion (n = 2), transient visual loss (n= 1) and per study protocol (n = 1). The reason to discontinued IFNα treatment was related with worsening retinopathy.

Discussion

Interferons belong to a large group of glycoproteins with antiviral, anti-tumour and immune modulatory effects. Upon contact with a virus, innate immune system activates and produces cytokines, chemokines and IFNs. IFNs turn on hundreds of interferon-stimulating genes (ISGs) through JAK-STAT pathway. The products of ISGs act on multiple steps of viral life cycle to counter replication. Side effects of IFNs include influenza-like syndrome, haematological, psychiatric, cardiovascular, endocrine and ophthalmological abnormalities. The exact mechanism of IFN-associated retinopathy is not known. Ikebe and colleagues reported the first case of IFN-associated retinopathy in a 39-year-old woman who developed cotton wool spots and retinal haemorrhages after intravenous administration of IFN in 1990.[26] In 1993, Miller et al.[27] showed that systemic administration of IFNα successfully inhibited angiogenesis in an experimental model of iris neovascularization. For its antiangiogenic effects, IFNα has been used to stop the subretinal neovascularization in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration.[28] Later, Guyer et al.[29] used fluorescein angiography in patients who developed retinopathy after IFN administration for reasons other than HCV and showed areas of retinal ischaemia and poor perfusion. Nishiwaki et al.[30] showed increased trapping of leucocytes in the retinal microcirculation of rats after the administration of IFNα. The trapping of leucocytes was dose dependent; the authors postulated that this might be related to impairment of the retinal microcirculation. Nagaoka et al.[13] studied the effects of IFN on retinal microcirculation in patients with chronic HCV receiving treatment. They showed that wall shear stress increased significantly within 2 weeks of treatment initiation. Their findings suggested endothelial dysfunction as a cause of IFN-associated retinopathy. IFN-associated retinopathy was more frequent in patients with DM or HTN in the previously reported studies.

Abe et al.[31] demonstrated that patients with chronic HCV infection had a higher incidence of retinopathy compared with the age- and sex-matched controls, independent of the IFN treatment. Similarly, Purtscher-like retinopathy was reported in a chronic HCV patient with cryoglobulinemia who was not on IFN treatment. Authors of the above two studies suggested an immune complex mediated ischaemic injury to the retina. HCV has been isolated from the lacrimal secretions and tears of the patients with chronic HCV infection,[32] but we do not know of any study demonstrating active replication of HCV in the retinal epithelial cells causing retinopathy.

The incidence of retinopathy related to IFNα or PegIFNα has been variably reported in the literature, and there is no consensus on screening and surveillance protocols in such patients.[4, 8, 9] A recent study by Vujosevic et al.[4] reported a very high incidence (30%) of retinopathy in 97 patients with chronic HCV during PegIFNα and ribavirin treatment. The frequency of the development of retinopathy was even higher among hypertensive patients (68%) during serial ophthalmological examination. Based on these findings, the authors not only recommended baseline ophthalmological examination in all patients with HTN but also serial fundoscopic examinations at 3-month intervals during the treatment period. They further suggested continuing the fundoscopic examination 3 months after the end of treatment if the patient developed any retinopathy during the treatment period, regardless of any visual symptoms. On the contrary, Panetta et al.[9] reported a very low incidence (3.8%) of retinopathy among 183 patients with chronic HCV treated with PegIFNα and ribavirin. Moreover, patients with HTN and DM were not at higher risk of IFN-associated retinopathy. The authors concluded that pretreatment and during treatment, fundoscopic examinations were not necessary in asymptomatic patients, even in the presence of HTN and DM. The study by Vujosvic et al. was prospective and evaluated both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, while the study by Panetta et al. was retrospective and ophthalmological examinations were only carried out in symptomatic patients. This wide variation in the frequency of retinopathy is due to the differences in study designs, patient population and protocols for evaluation of retinopathy.[4, 9]

The result of this systematic review highlights some important points (i) The overall incidence of retinopathy during IFN (IFNα and PegIFNα) treatment and ribavirin is around 27%. The risk is higher in patients treated with standard IFNα but much lower in patients treated with the current standard of care, PegIFNα. The precise mechanism by which IFN causes retinopathy is unknown, but it is thought to be related to microvascular changes in the retinal circulation.[4] The difference between the incidence of retinopathy between PegIFNα and IFNα may be explained by their pharmacokinetics. PegIFNα is a once a week subcutaneous injection with a steady release, and IFNα is administered at least three times a week with a shorter half-life and higher peak concentration. (ii) The risk of development of retinopathy in patients without DM and HTN is low, and the frequency of retinopathy increases with coexisting DM and HTN. (iii) The IFN-related retinopathy is not a progressive disease, and most of the patients had spontaneous resolution of retinopathy after finishing the treatment. (iv) A significant number of patients developed retinopathy on treatment with IFN, but only a few patients discontinued treatment. In our literature review, only three patients in the PegIFNα group had to discontinue treatment due to worsening retinopathy, and all three of them developed visual symptoms during the treatment. The other five patients in the PegIFNα group discontinued treatment due to nonmedical reasons (patient preference and per study protocol). Even in the study of Vujosevic et al., despite a very high incidence of the retinopathy, only one patient had to stop treatment. This patient came to medical attention because he developed significant visual symptoms. It appears that the development of visual symptoms is a key finding during the treatment and necessitates a complete fundoscopic examination regardless of co-morbidities or pre-existing retinopathy.

The current study has limitations. Studies included had variable design and patient population giving rise to incidence rates with wide dispersion. We used random effects model for all our analysis to account for this heterogeneity. All the studies did not provide information about the presence of risk factors such as HTN and DM. Most of the studies also did not provide information regarding which patients had both HTN and DM.

In conclusion, pooled analysis of studies suggests that incidence of retinopathy with PegIFNα is low, especially among patients without underlying DM or HTN. Results also highlight that retinopathy is mostly a temporary and asymptomatic complication, if it is not associated with visual symptoms. Based on these findings, we recommend that baseline screening for retinopathy should only be performed in high-risk group (with HTN and DM) prior to the initiation of the treatment. Low-risk group does not need any baseline screening evaluation. Also, we recommend against the serial fundoscopic examinations in both high-risk and low-risk groups during the treatment. We recommend complete ophthalmological evaluation in any patient who develops visual symptoms during treatment.

References

-

Lewis H, Cunningham M, Foster G. Second generation direct antivirals and the way to interferon-free regimens in chronic HCV. Best Pract ResClin Gastroenterol 2012; 26: 471–485.

-

Martel-Laferriere V, Dieterich DT. Update on combinations of DAAs with and without pegylated-interferon and ribavirin: triple and quadruple therapy more than doubles SVR. Clin Liver Dis 2013; 17: 93–103.

-

Gane E. Future perspectives: towards interferon-free regimens for HCV. Antivir Ther 2012; 17: 1201–1210.

-

Vujosevic S, Tempesta D, Noventa F, Midena E, Sebastiani G. Pegylated interferon-associated retinopathy is frequent in hepatitis C virus patients with hypertension and justifies ophthalmologic screening. Hepatology 2012; 56: 455–463.

-

Narkewicz MR, Rosenthal P, Schwarz KB et al. Ophthalmologic complications in children with chronic hepatitis C treated with pegylated interferon. J Pediatr GastroenterolNutr 2010; 51: 183–186.

-

d'Alteroche L, Majzoub S, Lecuyer AI, Delplace MP, Bacq Y. Ophthalmologic side effects during alphainterferon therapy for viral hepatitis. J Hepatol 2006; 44: 56–61.

-

Neyeloff JL, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB. Meta-analyses and forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Res Notes 2012;5: 52.

-

Abd El-Badie Mohamed M, Abd-El Azeem Eed K. Retinopathy associated with interferon therapy in patients with hepatitis C virus. ClinOphthalmol 2012; 6: 1341–1345.

-

Panetta JD, Gilani N. Interferon-induced retinopathy and its risk in patients with diabetes and hypertension undergoing treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30: 597–602.

-

Fouad YM, Khalaf H, Ibraheem H, Rady H, Helmy AK. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C virus treated with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin. Int J Infect Dis 2012; 16: e67–e71.

-

Mehta N, Murthy UK, Kaul V, Alpert S, Abruzzese G, Teitelbaum C. Outcome of retinopathy in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon and ribavirin. Dig DisSci 2010; 55: 452–457.

-

Malik NN, Sheth HG, Ackerman N, Davies N, Mitchell SM. A prospective study of change in visual function in patients treated with pegylated interferon alpha for hepatitis C in the UK. Br J Ophthalmol 2008; 92: 256–258.

-

Nagaoka T, Sato E, Takahashi A, Yokohama S, Yoshida A. Retinal circulatory changes associated with interferon-induced retinopathy in patients with hepatitis C. Invest OphthalmolVis Sci 2007; 48: 368–375.

-

Andrade RJ, Gonzalez FJ, Vazquez L et al. Vascular ophthalmological side effects associated with antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C are related to vascular endothelial growth factor levels. Antivir Ther 2006; 11: 491–498.

-

Okuse C, Yotsuyanagi H, Nagase Y et al. Risk factors for retinopathy associated with interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:3756–3759.

-

Ogata H, Suzuki H, Shimizu K, Ishikawa H, Izumi N, Kurosaki M. Pegylated interferon-associated retinopathy in chronic hepatitis C patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2006; 50:293–295.

-

Chisholm JA, Williams G, Spence E et al. Retinal toxicity during pegylated alpha-interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C: a multifocal electroretinogram investigation. AlimentPharmacol Ther 2005; 21:723–732.

-

Cuthbertson FM, Davies M, McKibbin M. Is screening for interferon retinopathy in hepatitis C justified? Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 1518–1520.

-

Schulman JA, Liang C, Kooragayala LM, King J. Posterior segment complications in patients with hepatitis C treated with interferon and ribavirin. Ophthalmology 2003; 110:437–442.

-

Jain K, Lam WC, Waheeb S, Thai Q, Heathcote J. Retinopathy in chronic hepatitis C patients during interferon treatment with ribavirin. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 1171–1173.

-

Saito H, Ebinuma H, Nagata H et al. Interferon-associated retinopathy in a uniform regimen of natural interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Liver 2001; 21: 192–197.

-

Sugano S, Suzuki T, Watanabe M, Ohe K, Ishii K, Okajima T. Retinal complications and plasma C5a levels during interferon alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis C. AmJ Gastroenterol 1998; 93: 2441–2444.

-

Kawano T, Shigehira M, Uto H et al. Retinal complications during interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 309–313.

-

Hayasaka S, Fujii M, Yamamoto Y, Noda S, Kurome H, Sasaki M. Retinopathy and subconjunctival haemorrhage in patients with chronic viral hepatitis receiving interferon alfa. Br J Ophthalmol 1995; 79: 150–152.

-

Kim ET, Kim LH, Lee JI, Chin HS. Retinopathy in hepatitis C patients due to combination therapy with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Jpn J Opthalmol 2009; 53: 598–602.

-

Ikebe T, Nakatsuka K, Goto M, Sakai Y, Kageyama S. A case of retinopathy induced by intravenous administration of interferon. FoliaOpthalmol Jpn 1990; 41: 2291–2296.

-

Miller JW, Stinson WG, Folkman J. Regression of experimental iris neovascularization with systemic alfainterferon. Opthalmology 1993; 100: 9–14.

-

Fung WE. Interferon alfa 2a for treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Opthalmol 1991; 112: 349–350.

-

Guyer DR, Tiedeman J, Yannuzzi LA et al. Iterferon-associated retinopathy. Arch Opthalmol 1993; 111: 350–356.

-

Nishiwaki H, Ogura Y, Miyamoto K, Matsuda N, Honda Y. Interferon alpha induces leukocytecapillary trapping in rat retinal microcirculation. Arch Opthalmol 1996; 114: 726–730.

-

Abe T, Nakajima A, Satoh N et al. Clinical characteristics of hepatitis C virus-associated retinopathy. Jpn JOpthalmol 1995; 39: 411–419.

-

Jacobi C, Wenkel H, Jacobi A, Korn K, Cursiefen C, Kruse FE. Hepatitis C and ocular surface disease. Am J Opthalmol 2007; 144: 705–711.

No comments:

Post a Comment